The Anglosphere

Interesting thought: “…almost all the advances of freedom in the 20th century have been made by the English-speaking peoples — Americans especially, but British, as well, and also … Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders.”

I remember a similar quote at the end of this article: "... the values that made America, and our sister nations of the Anglo-sphere, civilization’s bulwark against tyranny and barbarism over the last 200 years." And in this article: "While continental Europe descended into dictatorships, totalitarian horrors, and the Gulag, the Anglo-American tradition upheld the rule of law, parliamentary proceedings, and the individual liberties of speech, thought, and religion."

Defintely an interesting thought.

18 Comments:

This may be slightly more complex

and have its roots in English Common law.

Sorry to be off topic, Jason, but I wanted you to see this.

Also, look at "A World Without America," also at CUANAS.

Cubed here.

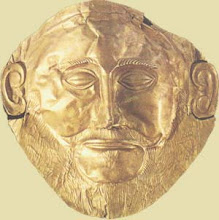

The pattern of the spread of the "advances of freedom" that have been made by the English-speaking peoples is as easy to see as the spread of Hellenism by the Greek conquests of antiquity.

Like Hellenism, born in Greece, the Enlightenment was born in one place: Britain (with a few contributions from the Continent, particularly Voltaire), and it followed the Brits as they established the British Empire. We, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada are the heirs of this process.

English Common Law was a "gene" on the "chromosome" of the evolution of the body of philosophic principles that culminated in the Enlightenment.

The other countries/cultures that have benefitted from their prolonged contact with the British (most famously, Hong Kong and India) have also benefitted from their experience. It would even seem that it is spreading to places like (gasp!) Communist China, the ultimate philosophic enemy of the right to private ownership of property (a product of the Enlightenment, spread around the world by the Brits).

Continental Europe just didn't participate very fully in the whole Enlightenment thing; Germany, especially, what with its admiration and loyalty to the likes of Kant, never was a part of the spread, although it benefitted indirectly from the fact that it existed right next door.

The philosophic "geneology" of the Renaissance through the present, and the "migratory routes" that spread it, is fascinating!

The American Revolution began with peasant riots in 13th Century England.

Yes, the British Enlighenment is the difference. One can see roots or hints of what's to come in English thinkers going back to the 12th century but it didn't solidify and become firmly established until the 17th and 18th century.

In the British Isles, the cultural change was broad and deep -- becoming part of the worldview of the general public.

Thanks, AOW, it's a worry. Given the lax attitude of the government and media I think it is a high probability in the next 10 years but perhaps in the near future.

I almost addressed these concerns last year when I wrote:

"The Revolutionary pamphleteers were not professional writers but common citizens engaged in the debate of ideas; they created a sense of democracy to the intellectual struggle that preceded the call to arms. In stark contrast was the French Revolution--debate was among the elites who often looked down on the general population as hopelessly retrograde. If the French Revolution started in salons, the American started in saloons ... and town squares, churches, etc. One ended with a stable republic; the other with Napoleon and what was basically a world war."

The British Enlightenment also was broad-based. In the century after Locke, his ideas were discussed in common venues and absorbed by the general population. England was often derided as a nation of shop-keepers and colonial America was populated by the farmer-citizen who was in tuned to the contemporary civic debates.

The Enlightenment intellectuals in France held Locke and the English form of government in high esteem (especially Montesquieu.) There were notable liberal writers through out continental Europe. However, there was always an elitist disconnect with the masses. I had some good quotes by French Enlightenment thinkers expressing their despair over the reactionary nature of the general population ... but I can't find them at the moment.

The continental intellectuals often depended on the good will of an enlightened monarch. But when the masses acted up, the monarch (or their successor) would clamp down. Nevertheless, there were many good minds on the continent. The term laissez-faire, after all, obviously comes from the French.

You're right that the nation-state came with ethnic cleansing but that was mostly due to religious wars. On the continent you'll find nearly homogeneous religious nation-states with a few exceptions. England, after Locke, tolerated many religions with the usual exception for Catholicism because of historical fears of Papal loyalty and influence.

Holland, by the way, should be closely associated with England. It was capitalist and had a tolerant atmosphere. Locke found haven there before the Glorious Revolution. Hugo Grotius was an important Enlightenment thinker. Spinoza, too!

The British Enlightenment was empirical in disposition even if the explicit epistemology of the Empiricists was problematic. However, this lends itself to a more bottoms-up approach. The Rationalist model in Europe is top-down. Descartes tries to deduce everything and finds it impossible without the grace of God. Rationalism failed on the first try. But the rationalist disposition, top-heavy with abstractions and loose on extensive examination of evidence, lends itself more easily to utopian schemes.

Kant and Rousseau are either considered Enlightenment figures or the first anti-Enlightenment figures. I'm in the latter camp. Rousseau's "general will" has a collectivist taint. And Kant's self-proclaimed Copernican Revolution takes the problems of the mind "reaching reality" as a "feature" of the solution instead of a "bug" that plagued prior philosophers of both the Rationalist and Empiricist schools. If reason is so emasculated one can hardly call Kant its champion. His ethics is problematic as well.

Yes, England and America can't compare to the continent in most of the arts, especially music. But in literature we have Shakespeare. I grant you he was prior to the Enlightenment but I wouldn't consider the literature of English writers in general to be second rate. I'm not quite sure why the less verbal arts are so much better in continental Europe. I won't dismiss the arts as unimportant. But I shy away from the topic out of modesty (if you can believe that!)

When a scientist attempts to explain physical processes, he does not begin by examining the myriad of processes, so as to derive conclusions. Rather, he finds a single process, or a few, for which there is an explanatory principle, be it for the melting of ice, or the falling of an apple. Then the scientist seeks more general laws or principles from which he derives the previous (subordinate) principles.

I see an analog in history, where first we need to develop general precepts, from which we can derive conclusions. Thus, I (who do not know much about history) would first try to ascertain the precepts at issue, and employ them to deal with subjects such as the causal effects of the English-speaking peoples (for whom I have the greatest respect, if only because I do poorly at other languages).

My view of history is that it is the story of the testing of ideas, by competing countries that have different concepts & values, so that in the final analysis it is their summa bonum that compete. I also believe that history is the victory of the few, against impossible odds. Finally, I see it as the unfolding of liberty & conscience.

It is on this basis that I would attempt to explain the superiority of the English-speaking peoples (although I lack the competence to do so). I hope that this discourse on method has not distracted from the present discussion. As with science, I aver that clarifying method is essential for deciding between conflicting analyses.

One can certainly see the dominance of the concept of individual rights in 18th century England and America. But this concept can be trace back to antiquity.

The story of Antigone involves the rights of the individual against the arbitrary power of the King. Aristotle distinguished between natural rights and positive rights but he didn't make natural rights central to his political analysis. The Stoics did and Cicero does an excellent job of putting forth a rich description. Aquinas champions natural law. Suarez, in Spain, is considered an important contributor to the tradition and influenced Hugo Grotius who influenced Locke.

Why didn't the idea take root in Italy or Spain when it first appeared in modern times? Why didn't the Spanish become the creators of liberal institutions instead of the English?

I don't fully know the reason but the result seems clear. In England the idea was absorbed by the population at large and became central to political life. Arguments based on natural rights had authority. The individual saw himself as an end in himself and not a tool of the state or church. This proud independent spirit permeated every corner of the English-speaking world. There were other ideas and amble contradictions but rights weren't just on the drawing board of some scholar or monk; they were operative ideas in the civic life of England and America.

Jason writes: "Why didn't the idea [of individual rights] take root in Italy or Spain when it first appeared in modern times? Why didn't the Spanish become the creators of liberal institutions instead of the English?

I don't fully know the reason but the result seems clear. In England the idea was absorbed by the population at large and became central to political life. Arguments based on natural rights had authority."

I appreciate Jason's method of analysis, as it describes the issue (regarding the English-speaking people) in terms of their acceptance of individual rights. With regard to why they adopted that aspiration, I would ground it in their previous concepts & values, while similarly deriving the lack of adoption by the Italians and Spanish by that same criteria. (To me the analysis would clearly show the deficiencies of the Italians by their concern with the passions of artistic esthetics, and of the Spanish by their passions of being conquistadors, and with both by their inability to speak English :) . Meanwhile the cold British, who lacked any passions, could dispassionately develop the concepts of rights, especially since they happened to be able to speak English :) . (Perhaps you can see why I am not a historian, as my key principle for analyzing national behavior is to adhere to stereotypes and ethnic slurs.)

As an aside, when the Spanish watched American films in the 1950s, they were disoriented by our Westerns, for they viewed our villains (who had rough voices, and rode dark horses) as looking like heroes, while viewing our heroes (who were clean-shaven, and rode white horses) as looking like villains.

However, regardless of the predisposition of a people to accept or reject ideas, there is also the role of individual and group choices. That is, history is not predetermined, so *many things could go one way or another, dependent on how well the few thinkers do their job*.

Yet again, regardless of my authoritative analysis, for whatever the reason the English rose to the occasion, the important thing (ala Jason) is that they did so, so 'Long live the king.'

Cubed here.

Jason,

"Why didn't the idea take root in Italy or Spain when it first appeared in modern times?"

I can't offer any ideas re: Italy, but one thing that profoundly influenced Spanish attitudes/values was its centuries under the heel of Islamic occupation experienced during the time when the rest of Europe was "at the ready" re: the Renaissance and what was to follow.

Ironic, isn't it, that it was Muslim collectors in Spain who brought what was left of Aristotle's works back to Europe, and that it was a Muslim, Ibn Rushd, the "Great Commentator," whose work on Aristotle was the primary source of the Aristotelian thinking that kick-started us out of the Dark Age.

Of course, his Muslim colleagues in North Africa ordered him banished for his efforts (how DARE he put the importance of reason above faith!), and quite possibly had him killed.

Spain was the westernmost outpost of Islam, and the strict fundamentalist ideas that characterize the Islam that we have grown to know and love today didn't grip Spain with the same stranglehold it held over the rest of Islam quite as early as it did in the Eastern Mediterrean and North Africa, but it wasn't far behind.

Ibn Rushd was Islam's last chance to take the fork in the road that would have permitted it to progress along the path of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, etc., but it elected not to choose that route.

So Spain was stuck with an increasingly stagnant philosophy that held revelation, not reason, as its epistemology, the means of acquiring knowledge; the spread of Islam over human life as its "standard of the good;" the whim of Allah over natural law as its metaphysics; and totalitarianism over human rights as its politics.

In - what was it, about 700 years? - of occupation by the Muslims, right up to the year Columbus sailed to the New World to try to find a quick infusion of wealth to get Spain out of the economic doldrums caused by the cost of the 300 or so years it took them to get rid of the Muslims, Spain had adsorbed (maybe even absorbed) a lot of attitudes, notion, habits, and even values of its Muslim masters.

By the time Spain was gearing up to find wealth in the New World, the rest of early Renaissance Europe had already made substantial gains in commerce, science, the arts, etc, thanks primarily to the works of Aristotle that had leaked into the rest of Europe, especially Italy, from libraries "liberated" a couple of centuries before the Muslims were officially out altogether.

Spain began to catch up quickly, but just as happened with the spread of Hellenism via Alexander the Great, and with the Enlightenment via the British Empire, the 700 years (or thereabouts) of Muslim influence stuck around in Spain and was spread to Central and South America with the Conquistadors and those who followed them (albeit under a "Spanish" label, not a strictly "Muslim" label). Even the common greeting, "Ola!" is a corruption of "Allah."

The Conquistadors began the spread of the Islam-tainted Spanish influence in the New World a mere 20 or so years after Columbus, just after they kicked out the Muslims, and it lingers in the Hispanic New World to this day.

So many things in Spanish culture still hang on as cultural relics of their "Muslim Experience" - a pronounced machismo, the open acceptance of "second families," a feudal organization of society, a caste system, much of their music and architecture, etc.

I want to take the time someday to do the research, but I don't think it's out of the question to think that some of the hugs-and-kisses between Hispanic American and Iran, Hamas, al-Qaeda, and Hizbollah aren't a hangover, a remaining shred of a sense of philosophical "species solidarity," between Hispanic America and Islam, and of the enmity that it has for the Enlightenment English-speaking world and its Continental sidekicks.

Winston Churchill's book, History of the English Speaking Peoples is a worthwhile read.

The Conquistadors began the spread of the Islam-tainted Spanish influence in the New World a mere 20 or so years after Columbus, just after they kicked out the Muslims, and it lingers in the Hispanic New World to this day.

Cubed's comment about Spain is very interesting--all of it, not just the above excerpt.

As a Spanish major, I agree with much of what she has said.

In fact, when I was in college, one of my professors (from Andalucia and a real hunk) told us point-blank that Spain was forever corrupted by the Moors--even long after the Moors were expelled. He felt that the Spanish obsession with acquiring gold had its roots in the idea that enough wealth could prevent another Muslim conquest. He went on to say, in those days when being politically incorrect was not a problem on campus, that the cruelty of the Conquistadors was directly related to Moorish blood. This from a fellow who admitted that in his own veins flowed that same blood. Of course, as a devout Roman Catholic, he also believed that his Christianity kept the more sinister elements of his personality in check.

BTW, this professor's speciality was the medieval literature of Spain. That period contains much material offensive to Muslims.

I've read that many of the techniques used in the Spanish Inquisition derived from some of the Moors' torture techniques used against Christians as the Iberian Peninsula succumbed to the boot of the Moor.

According to Michener, the Moorish rule of Spain forever changed the tone of the nation. In many ways, Spain is not, even today, a part of Europe.

AOW is insightful in noting the Moorish influence on Spain, and writes "In many ways, Spain is not, even today, a part of Europe."

Yet have heart, since Europe is incorporating its Muslim influence. In not very long, Eurabia and Spain will become more similar.

I'm not as familiar with Spanish history to comment. I wonder what Martinito could tell us (if he stops by).

Thanks, Social Sense, I've wanted to read Churchill's history. I read his speeches but I haven't gotten to his History of the English Speaking People. Clearly a gap in my knowledge.

Unfortunately the corrupted Iberian culture is entering through the southern border during the "Hispanification" of California and the Southwest as the "new people" migrating from the south are bringing with them elements of their culture that are compatible with American-style democracy.

The problem is acute because the continual flow does not allow time for assimilation and dual citizenship allows them to maintain and promote the interests of the old country.

Islbela, the best "king" of Spain would never have permitted this situation to continue. The reason for the expulsion of the Jews and Moriscos was to create a homogenous culture and to prevent sedition and sabotage, a lesson we have learned from her example.

Isabela is often labeled the "best 'king' of Spain' because of her strong personality and decisive actions at the beginning of the restructuring of Spain after the reconquista.

A very interesting read.

Anglosphere countries are ones I would trust.

Cubed offered some reasons why Spain has lagged England and other parts of Europe in its embrace of reason and freedom. In essence she blames Islam. I wont argue that Islam contributed but I would say that Spain's lag is because of Christianity. England was able to suppress its Christian elements more fully and embrace reason. Spain could not. Christianity's hold on the nation was too strong. I also blame Christianity not Islam for the sorry plight of Central and South America.

I find it disappointing that an Objectivist would be an apologist for Christianity.

Post a Comment

<< Home