Civilization faces the threat of a resurgent Islam, a vast growing movement to revive the jihadist ideals exemplified by Islam’s founder, Mohammad, and the imperialist warrior ideology of the early Caliphate. Amidst the vast denial of Islam’s inherent threat to civilization, there are two distinct but related intellectual camps that are able to face the harsh reality of this vicious ideology. One camp fights Islam under the banner of the Enlightenment while the other waves the flag of the Judeo-Christian tradition. The purpose of this article is to describe these two different approaches, how they grapple with the jihadist ideology, and how they arrive at much the same conclusion but organize their knowledge around different conceptual centers.

The Enlightenment Viewpoint

The Enlightenment camp is a broad group that includes secular classical liberals and modern left-liberals. In both sub-groups there is an emphasis on Islam as a religious reductio ad absurdum that rejects reason for blind faith, disparages reality for an after-life in another realm, banishes independent thought in submission to a dogmatic tradition, and prohibits individual liberty to establish religious theocracy. Islam is an example of a full and consistent rejection of the core virtue of Western culture whose roots go back to Ancient Greece: rationality. The Enlightenment critique centers the analysis on process: reason, empiricism, skepticism, and liberty—the high points of the Anglo-American Enlightenment and shared to some extent by the Continental Enlightenment before its decent into the collectivist/relativist decay of the 19th and 20th century.

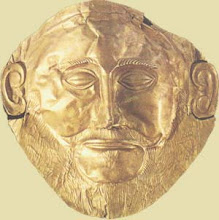

The spirit is captured by Thomas Jefferson: “Fix reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason than that of blindfolded fear." The Enlightenment camp, as a very broad group, advocates the primacy of reason as the means to understand nature, both natural and social. The origin of reason to human affairs originated in Ancient Greece after philosophy moved from the cosmological period to the anthropological period; Socrates countered the relativists of his day, the Sophists, by arguing that philosophy can establish ethical knowledge to govern human affairs. Aristotle wrote the first treatise on ethics in human history; he applied Hellenic rationalism to natural observations of human flourishing and character excellence.

The Latin Christian tradition absorbed Hellenic rationalism in a fundamental manner that Orthodox Christians failed to do. Thomas Aquinas championed Aristotle thereby setting the foundation for a transformation of Western thought. Aristotle’s potent empiricism (for example Darwin admired his biological studies) was at times little understood as his work was unfairly associated with the faults of the Catholic Church. However, in human affairs, the founding fathers were arduous students of political history in a manner reminiscent of Aristotle exhaustive study of the constitutions of his day.

In ethical and political thought, the Anglo-American tradition’s empirical disposition, while not without its faults, remained grounded in a reality-based practice that avoided the extremes of continental collectivist ideology. The privatization of religion leaves the common ground of social affairs within the realm of rational discourse. Even America’s traditionalist conservatives speak of religion as a disposition. Talking about religion at the time of the American Revolution, Paul Johnson, in A History of the American People, says it was a “specifically American form of Christianity – undogmatic, moralistic rather than creedal, tolerant but strong … an ecumenical and American type of religious devotion …”

Today, we see the Enlightenment critique of Islam in books by Sam Harris and Ibn Warraq; and in articles by David Kelley and Peter Schwartz. It is common in Europe where Pim Fortuyn, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Oriana Fallaci attack Islam from a secular perspective.

The Judeo-Christian Critique of Islam.

While the secular Enlightenment camp rightly points to a vast difference—of degree—between Western religions and Islam, the critics of Judeo-Christian camp will insist there is a difference in kind. If the secular camp critiques Islam’s backwardness based on process—a faith fully consuming and preempting rational reality-based thought—the Judeo-Christian critic immediate zooms in on the content: the ethical doctrines and myths of the Islamic faith.

Islam’s origin and its key figure are unique: rarely in history does one find a religion founded by a warrior and dominated by that example. Mohammad set a very different example than Jesus. Mohammad was a man of war who committed atrocities in his quest to create a culture of domination, submission and servitude. This is clearly not a moral man by any stretch of the imagination.

The Judeo-Christian camp sees the West’s moral base derived from the Bible; and religion as the only foundation for morality. Modern secularism is dominated by relativism and materialism, which holds that human nature, lacking volition, needs no code of ethics; nature or nurture determines individual character. This no-fault worldview is a nihilistic attack on traditional American values. In the Judeo-Christian camp is Lawrence Auster, Joseph Farah, Robert Spencer, Paul M. Weyrich, Don Feder, etc.

The Western tradition, however, is Greco-Roman as well as Judeo-Christian. It is far from trivial to do an attribution analysis. St. Paul, whose writing comprises 40% of the New Testament, was an educated Hellenistic Jew. Augustine was educated in Greek and Roman philosophy. Aquinas is one of history’s foremost scholars of Aristotle. Traditionalists tend to respect the totality under the banner of Western Civilization. But by doing so they have often been the standard bearers, by default, of much of the Hellenic inheritance as post-modern intellectuals exhibit a hostility to the Aristotelian worldview—and the American ideals.

Content vs. Process

Both camps correctly see Islam as an outlier. For the Enlightenment camp, Islam differs from modernity by being religious and Islam differs from today’s Christianity by a vast difference in degree. For the Judeo-Christian camp, Islam differs from Christianity by being a different kind of a religious ideology inspired by a completely different kind of prophet. These two camps differ on how they’d describe the core nature of the West: reason based on our Greco-Roman secular heritage or religious morality based on our Judeo-Christian heritage.

The differences between Islam and Christianity, in content, create extra hurdles for Islam that prohibit any significant integration with reason and modernity. Moderation in Arab and Muslim nations in the past has come with Islam’s marginalization. Islam is inherently an illiberal political ideology. In terms of doctrine, it has far less play to allow the emergence of a large-scale sustainable moderate yet profoundly religious practice. However, the relationship between the intractable illiberal oppressiveness of Islam and its extreme practice of intellectual submission to dogma and authority are intimately related. Such oppressive backwardness, given what mankind has achieved in every sphere of human activity, requires a mind closed to reason, pumped-up with irrational hate, and frozen by fear.

Islam requires extreme blind faith and obedience because of the extent that its teachings are at odds with living a full life in a free society. If Islam is to be practiced in full, and not merely perfunctory or selectively practiced, it will lead to continued impoverishment, oppression, war, and death. It is interesting that the post-modern left, to retain its dream of socialism after all the evidence of its failure and capitalism’s success, needs to maintain the epistemologically nihilistic doctrine of postmodernism that denounces the very concept of truth. Both flee from reality to hold on to cherish dogma. And they are united by a common enemy: America.

The Challenges for Each Camp.

Secular critics need to avoid a conflation of Islam and Christianity that is achieved by ignoring the vast differences of degree. This is common with the multi-cultural left that either claims Christianity is no better or that Islam is no worse. This absurdly ignores reality: Christians today aren’t driven by a religious fervor to fly planes into buildings, killing peaceful members of civilization, in an attempt to take the world back to the Dark Ages. And Islamic nations have not established tolerance societies that respect individual rights, reason and science except for transitory isolated exceptions. Furthermore, to claim that Islam has the potentiality to reform like Christianity can not be asserted a priori. Upon investigation there are severe barriers due to the specific content of Islam that makes such prospects a pipedream. To ignore the vast differences between the religions of Islam and Christianity obliterates crucial distinctions that serve no other purpose but to drive a needless wedge between secular and Christian opponents of Islam.

The relativist left buckles under the weight of its moral skepticism and inability to trumpet our superiority over barbaric cultures like Islam. Their approach is a dead end both figuratively and literally. Those approaching the Islamic threat from a secular perspective have to rely on the certainly of moral absolutes that were standard in secular philosophic thought before the subjectivism of the last two centuries. Tolerance of rights isn’t based on moral skepticism. Nothing follows from wholesale skepticism.

The religious camp faces a challenge it has assiduously hoped to avoid: the examination of the doctrines of different religions. Traditionalists once Anglo-American culture was described as Protestant (with a Calvinist emphasis), then Christian (to include Catholics) and finally Judeo-Christian (to include Jews.) The ecumenical spirit required glossing over differences in content. This general disposition embodied the notion that all long-established religions held the equally valid moral traditions. Communism helped convince many that this was true. The resurgence of Islam threatens the ecumenical spirit. To delve into the content of this religion opens a Pandora’s Box that conservatives instinctively fear may revive religious disharmony.

However, the ecumenical spirit is unnecessary if religion is a private matter. If public disputes are subject to reality-checks applying reason to human history and appreciating the ethical principles that make civilization possible, we can settle disputes and live in harmony. Private matters, like religion, remain private. Thus, the secularization of society protected by individual rights makes a natural diversity possible. Islam, being inherently a political ideology, is incompatible with a pluralistic secular society of equal rights and mutual respect.

In Summary

A worldview isn’t created or altered by simple arguments; it is an integrating philosophy that spans a lifetime. The threat of Islam, like the threat of communism for previous generations, will encourage us to take stock of our cultural resources and strengths. The first order of business is to fact the fact that there is a vast difference between them and us; then we can move on to the question of what has made our culture great. The latter should be an enjoyable and ongoing debate. Taking inventory at this stage shows core groups in every camp are up to the challenge but we have a majority of people who are still in denial about the severity of the problem—for several reasons some of which were mentioned above.

In summary, the two approaches emphasize two aspects of the same problem, process and content. Blind faith is required to support an oppressive religious ideology. The nature of Islam requires this methodology. Religion in the West has accepted the coin of reason in everyday affairs while the Greco-Roman tradition, which dominated secular thought before the rise of relativism, provided a solid foundation for the ethical truths that were once widely accepted. Islam fails to fit with neither contemporary tolerant Christianity nor traditional Enlightenment rationality. Islam is the odd man out. As we avoid secular relativism, promiscuous religious ecumenicalism, and religious dogmatism, we can unite against the common threat.